This guide is intended to give an elementary description of ripgrep and an overview of its capabilities. This guide assumes that ripgrep is installed and that readers have passing familiarity with using command line tools. This also assumes a Unix-like system, although most commands are probably easily translatable to any command line shell environment.

- Basics

- Recursive search

- Automatic filtering

- Manual filtering: globs

- Manual filtering: file types

- Replacements

- Configuration file

- File encoding

- Common options

ripgrep is a command line tool that searches your files for patterns that you give it. ripgrep behaves as if reading each file line by line. If a line matches the pattern provided to ripgrep, then that line will be printed. If a line does not match the pattern, then the line is not printed.

The best way to see how this works is with an example. To show an example, we need something to search. Let's try searching ripgrep's source code. First grab a ripgrep source archive from https://github.com/BurntSushi/ripgrep/archive/0.7.1.zip and extract it:

$ curl -LO https://github.com/BurntSushi/ripgrep/archive/0.7.1.zip

$ unzip 0.7.1.zip

$ cd ripgrep-0.7.1

$ ls

benchsuite grep tests Cargo.toml LICENSE-MIT

ci ignore wincolor CHANGELOG.md README.md

complete pkg appveyor.yml compile snapcraft.yaml

doc src build.rs COPYING UNLICENSE

globset termcolor Cargo.lock HomebrewFormula

Let's try our first search by looking for all occurrences of the word fast

in README.md:

$ rg fast README.md

75: faster than both. (N.B. It is not, strictly speaking, a "drop-in" replacement

88: color and full Unicode support. Unlike GNU grep, `ripgrep` stays fast while

119:### Is it really faster than everything else?

124:Summarizing, `ripgrep` is fast because:

129: optimizations to make searching very fast.

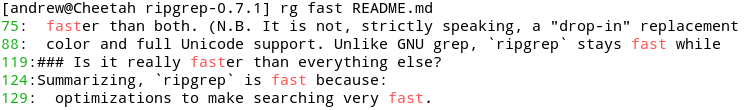

So what happened here? ripgrep read the contents of README.md, and for each

line that contained fast, ripgrep printed it to your terminal. ripgrep also

included the line number for each line by default. If your terminal supports

colors, then your output might actually look something like this screenshot:

In this example, we searched for something called a "literal" string. This

means that our pattern was just some normal text that we asked ripgrep to

find. But ripgrep supports the ability to specify patterns via regular

expressions. As an example,

what if we wanted to find all lines have a word that contains fast followed

by some number of other letters?

$ rg 'fast\w+' README.md

75: faster than both. (N.B. It is not, strictly speaking, a "drop-in" replacement

119:### Is it really faster than everything else?

In this example, we used the pattern fast\w+. This pattern tells ripgrep to

look for any lines containing the letters fast followed by one or more

word-like characters. Namely, \w matches characters that compose words (like

a and L but unlike . and ). The + after the \w means, "match the

previous pattern one or more times." This means that the word fast won't

match because there are no word characters following the final t. But a word

like faster will. faste would also match!

Here's a different variation on this same theme:

$ rg 'fast\w*' README.md

75: faster than both. (N.B. It is not, strictly speaking, a "drop-in" replacement

88: color and full Unicode support. Unlike GNU grep, `ripgrep` stays fast while

119:### Is it really faster than everything else?

124:Summarizing, `ripgrep` is fast because:

129: optimizations to make searching very fast.

In this case, we used fast\w* for our pattern instead of fast\w+. The *

means that it should match zero or more times. In this case, ripgrep will

print the same lines as the pattern fast, but if your terminal supports

colors, you'll notice that faster will be highlighted instead of just the

fast prefix.

It is beyond the scope of this guide to provide a full tutorial on regular expressions, but ripgrep's specific syntax is documented here: https://docs.rs/regex/0.2.5/regex/#syntax

In the previous section, we showed how to use ripgrep to search a single file. In this section, we'll show how to use ripgrep to search an entire directory of files. In fact, recursively searching your current working directory is the default mode of operation for ripgrep, which means doing this is very simple.

Using our unzipped archive of ripgrep source code, here's how to find all

function definitions whose name is write:

$ rg 'fn write\('

src/printer.rs

469: fn write(&mut self, buf: &[u8]) {

termcolor/src/lib.rs

227: fn write(&mut self, b: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> {

250: fn write(&mut self, b: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> {

428: fn write(&mut self, b: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> { self.wtr.write(b) }

441: fn write(&mut self, b: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> { self.wtr.write(b) }

454: fn write(&mut self, buf: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> {

511: fn write(&mut self, buf: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> {

848: fn write(&mut self, buf: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> {

915: fn write(&mut self, buf: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> {

949: fn write(&mut self, buf: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> {

1114: fn write(&mut self, buf: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> {

1348: fn write(&mut self, buf: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> {

1353: fn write(&mut self, buf: &[u8]) -> io::Result<usize> {

(Note: We escape the ( here because ( has special significance inside

regular expressions. You could also use rg -F 'fn write(' to achieve the

same thing, where -F interprets your pattern as a literal string instead of

a regular expression.)

In this example, we didn't specify a file at all. Instead, ripgrep defaulted

to searching your current directory in the absence of a path. In general,

rg foo is equivalent to rg foo ./.

This particular search showed us results in both the src and termcolor

directories. The src directory is the core ripgrep code where as termcolor

is a dependency of ripgrep (and is used by other tools). What if we only wanted

to search core ripgrep code? Well, that's easy, just specify the directory you

want:

$ rg 'fn write\(' src

src/printer.rs

469: fn write(&mut self, buf: &[u8]) {

Here, ripgrep limited its search to the src directory. Another way of doing

this search would be to cd into the src directory and simply use rg 'fn write\(' again.

After recursive search, ripgrep's most important feature is what it doesn't search. By default, when you search a directory, ripgrep will ignore all of the following:

- Files and directories that match the rules in your

.gitignoreglob pattern. - Hidden files and directories.

- Binary files. (ripgrep considers any file with a

NULbyte to be binary.) - Symbolic links aren't followed.

All of these things can be toggled using various flags provided by ripgrep:

- You can disable

.gitignorehandling with the--no-ignoreflag. - Hidden files and directories can be searched with the

--hiddenflag. - Binary files can be searched via the

--text(-afor short) flag. Be careful with this flag! Binary files may emit control characters to your terminal, which might cause strange behavior. - ripgrep can follow symlinks with the

--follow(-Lfor short) flag.

As a special convenience, ripgrep also provides a flag called --unrestricted

(-u for short). Repeated uses of this flag will cause ripgrep to disable

more and more of its filtering. That is, -u will disable .gitignore

handling, -uu will search hidden files and directories and -uuu will search

binary files. This is useful when you're using ripgrep and you aren't sure

whether its filtering is hiding results from you. Tacking on a couple -u

flags is a quick way to find out. (Use the --debug flag if you're still

perplexed, and if that doesn't help,

file an issue.)

ripgrep's .gitignore handling actually goes a bit beyond just .gitignore

files. ripgrep will also respect repository specific rules found in

$GIT_DIR/info/exclude, as well as any global ignore rules in your

core.excludesFile (which is usually $XDG_CONFIG_HOME/git/ignore on

Unix-like systems).

Sometimes you want to search files that are in your .gitignore, so it is

possible to specify additional ignore rules or overrides in a .ignore

(application agnostic) or .rgignore (ripgrep specific) file.

For example, let's say you have a .gitignore file that looks like this:

log/

This generally means that any log directory won't be tracked by git.

However, perhaps it contains useful output that you'd like to include in your

searches, but you still don't want to track it in git. You can achieve this

by creating a .ignore file in the same directory as the .gitignore file

with the following contents:

!log/

ripgrep treats .ignore files with higher precedence than .gitignore files

(and treats .rgignore files with higher precdence than .ignore files).

This means ripgrep will see the !log/ whitelist rule first and search that

directory.

Like .gitignore, a .ignore file can be placed in any directory. Its rules

will be processed with respect to the directory it resides in, just like

.gitignore.

For a more in depth description of how glob patterns in a .gitignore file

are interpreted, please see man gitignore.

In the previous section, we talked about ripgrep's filtering that it does by

default. It is "automatic" because it reacts to your environment. That is, it

uses already existing .gitignore files to produce more relevant search

results.

In addition to automatic filtering, ripgrep also provides more manual or ad hoc filtering. This comes in two varieties: additional glob patterns specified in your ripgrep commands and file type filtering. This section covers glob patterns while the next section covers file type filtering.

In our ripgrep source code (see Basics for instructions on how to

get a source archive to search), let's say we wanted to see which things depend

on clap, our argument parser.

We could do this:

$ rg clap

[lots of results]

But this shows us many things, and we're only interested in where we wrote

clap as a dependency. Instead, we could limit ourselves to TOML files, which

is how dependencies are communicated to Rust's build tool, Cargo:

$ rg clap -g '*.toml'

Cargo.toml

35:clap = "2.26"

51:clap = "2.26"

The -g '*.toml' syntax says, "make sure every file searched matches this

glob pattern." Note that we put '*.toml' in single quotes to prevent our

shell from expanding the *.

If we wanted, we could tell ripgrep to search anything but *.toml files:

$ rg clap -g '!*.toml'

[lots of results]

This will give you a lot of results again as above, but they won't include

files ending with .toml. Note that the use of a ! here to mean "negation"

is a bit non-standard, but it was chosen to be consistent with how globs in

.gitignore files are written. (Although, the meaning is reversed. In

.gitignore files, a ! prefix means whitelist, and on the command line, a

! means blacklist.)

Globs are interpreted in exactly the same way as .gitignore patterns. That

is, later globs will override earlier globs. For example, the following command

will search only *.toml files:

$ rg clap -g '!*.toml' -g '*.toml'

Interestingly, reversing the order of the globs in this case will match nothing, since the presence of at least one non-blacklist glob will institute a requirement that every file searched must match at least one glob. In this case, the blacklist glob takes precedence over the previous glob and prevents any file from being searched at all!

Over time, you might notice that you use the same glob patterns over and over. For example, you might find yourself doing a lot of searches where you only want to see results for Rust files:

$ rg 'fn run' -g '*.rs'

Instead of writing out the glob every time, you can use ripgrep's support for file types:

$ rg 'fn run' --type rust

or, more succinctly,

$ rg 'fn run' -trust

The way the --type flag functions is simple. It acts as a name that is

assigned to one or more globs that match the relevant files. This lets you

write a single type that might encompass a broad range of file extensions. For

example, if you wanted to search C files, you'd have to check both C source

files and C header files:

$ rg 'int main' -g '*.{c,h}'

or you could just use the C file type:

$ rg 'int main' -tc

Just as you can write blacklist globs, you can blacklist file types too:

$ rg clap --type-not rust

or, more succinctly,

$ rg clap -Trust

That is, -t means "include files of this type" where as -T means "exclude

files of this type."

To see the globs that make up a type, run rg --type-list:

$ rg --type-list | rg '^make:'

make: *.mak, *.mk, GNUmakefile, Gnumakefile, Makefile, gnumakefile, makefile

By default, ripgrep comes with a bunch of pre-defined types. Generally, these types correspond to well known public formats. But you can define your own types as well. For example, perhaps you frequently search "web" files, which consist of Javascript, HTML and CSS:

$ rg --type-add 'web:*.html' --type-add 'web:*.css' --type-add 'web:*.js' -tweb title

or, more succinctly,

$ rg --type-add 'web:*.{html,css,js}' -tweb title

The above command defines a new type, web, corresponding to the glob

*.{html,css,js}. It then applies the new filter with -tweb and searches for

the pattern title. If you ran

$ rg --type-add 'web:*.{html,css,js}' --type-list

Then you would see your web type show up in the list, even though it is not

part of ripgrep's built-in types.

It is important to stress here that the --type-add flag only applies to the

current command. It does not add a new file type and save it somewhere in a

persistent form. If you want a type to be available in every ripgrep command,

then you should either create a shell alias:

alias rg="rg --type-add 'web:*.{html,css,js}'"

or add --type-add=web:*.{html,css,js} to your ripgrep configuration file.

(Configuration files are covered in more detail later.)

ripgrep provides a limited ability to modify its output by replacing matched

text with some other text. This is easiest to explain with an example. Remember

when we searched for the word fast in ripgrep's README?

$ rg fast README.md

75: faster than both. (N.B. It is not, strictly speaking, a "drop-in" replacement

88: color and full Unicode support. Unlike GNU grep, `ripgrep` stays fast while

119:### Is it really faster than everything else?

124:Summarizing, `ripgrep` is fast because:

129: optimizations to make searching very fast.

What if we wanted to replace all occurrences of fast with FAST? That's

easy with ripgrep's --replace flag:

$ rg fast README.md --replace FAST

75: FASTer than both. (N.B. It is not, strictly speaking, a "drop-in" replacement

88: color and full Unicode support. Unlike GNU grep, `ripgrep` stays FAST while

119:### Is it really FASTer than everything else?

124:Summarizing, `ripgrep` is FAST because:

129: optimizations to make searching very FAST.

or, more succinctly,

$ rg fast README.md -r FAST

[snip]

In essence, the --replace flag applies only to the matching portion of text

in the output. If you instead wanted to replace an entire line of text, then

you need to include the entire line in your match. For example:

$ rg '^.*fast.*$' README.md -r FAST

75:FAST

88:FAST

119:FAST

124:FAST

129:FAST

Alternatively, you can combine the --only-matching (or -o for short) with

the --replace flag to achieve the same result:

$ rg fast README.md --only-matching --replace FAST

75:FAST

88:FAST

119:FAST

124:FAST

129:FAST

or, more succinctly,

$ rg fast README.md -or FAST

[snip]

Finally, replacements can include capturing groups. For example, let's say

we wanted to find all occurrences of fast followed by another word and

join them together with a dash. The pattern we might use for that is

fast\s+(\w+), which matches fast, followed by any amount of whitespace,

followed by any number of "word" characters. We put the \w+ in a "capturing

group" (indicated by parentheses) so that we can reference it later in our

replacement string. For example:

$ rg 'fast\s+(\w+)' README.md -r 'fast-$1'

88: color and full Unicode support. Unlike GNU grep, `ripgrep` stays fast-while

124:Summarizing, `ripgrep` is fast-because:

Our replacement string here, fast-$1, consists of fast- followed by the

contents of the capturing group at index 1. (Capturing groups actually start

at index 0, but the 0th capturing group always corresponds to the entire

match. The capturing group at index 1 always corresponds to the first

explicit capturing group found in the regex pattern.)

Capturing groups can also be named, which is sometimes more convenient than using the indices. For example, the following command is equivalent to the above command:

$ rg 'fast\s+(?P<word>\w+)' README.md -r 'fast-$word'

88: color and full Unicode support. Unlike GNU grep, `ripgrep` stays fast-while

124:Summarizing, `ripgrep` is fast-because:

It is important to note that ripgrep will never modify your files. The

--replace flag only controls ripgrep's output. (And there is no flag to let

you do a replacement in a file.)

It is possible that ripgrep's default options aren't suitable in every case. For that reason, and because shell aliases aren't always convenient, ripgrep supports configuration files.

Setting up a configuration file is simple. ripgrep will not look in any

predetermined directory for a config file automatically. Instead, you need to

set the RIPGREP_CONFIG_PATH environment variable to the file path of your

config file. Once the environment variable is set, open the file and just type

in the flags you want set automatically. There are only two rules for

describing the format of the config file:

- Every line is a shell argument, after trimming ASCII whitespace.

- Lines starting with

#(optionally preceded by any amount of ASCII whitespace) are ignored.

In particular, there is no escaping. Each line is given to ripgrep as a single command line argument verbatim.

Here's an example of a configuration file, which demonstrates some of the formatting peculiarities:

$ cat $HOME/.ripgreprc

# Don't let ripgrep vomit really long lines to my terminal.

--max-columns=150

# Add my 'web' type.

--type-add

web:*.{html,css,js}*

# Set the colors.

--colors=line:none

--colors=line:style:bold

# Because who cares about case!?

--smart-case

When we use a flag that has a value, we either put the flag and the value on

the same line but delimited by an = sign (e.g., --max-columns=150), or we

put the flag and the value on two different lines. This is because ripgrep's

argument parser knows to treat the single argument --max-columns=150 as a

flag with a value, but if we had written --max-columns 150 in our

configuration file, then ripgrep's argument parser wouldn't know what to do

with it.

Putting the flag and value on different lines is exactly equivalent and is a matter of style.

Comments are encouraged so that you remember what the config is doing. Empty lines are OK too.

So let's say you're using the above configuration file, but while you're at a

terminal, you really want to be able to see lines longer than 150 columns. What

do you do? Thankfully, all you need to do is pass --max-columns 0 (or -M0

for short) on the command line, which will override your configuration file's

setting. This works because ripgrep's configuration file is prepended to the

explicit arguments you give it on the command line. Since flags given later

override flags given earlier, everything works as expected. This works for most

other flags as well, and each flag's documentation states which other flags

override it.

If you're confused about what configuration file ripgrep is reading arguments

from, then running ripgrep with the --debug flag should help clarify things.

The debug output should note what config file is being loaded and the arugments

that have been read from the configuration.

Finally, if you want to make absolutely sure that ripgrep isn't reading a

configuration file, then you can pass the --no-config flag, which will always

prevent ripgrep from reading extraneous configuration from the environment,

regardless of what other methods of configuration are added to ripgrep in the

future.

Text encoding is a complex topic, but we can try to summarize its relevancy to ripgrep:

- Files are generally just a bundle of bytes. There is no reliable way to know their encoding.

- Either the encoding of the pattern must match the encoding of the files being searched, or a form of transcoding must be performed converts either the pattern or the file to the same encoding as the other.

- ripgrep tends to work best on plain text files, and among plain text files, the most popular encodings likely consist of ASCII, latin1 or UTF-8. As a special exception, UTF-16 is prevalent in Windows environments

In light of the above, here is how ripgrep behaves:

- All input is assumed to be ASCII compatible (which means every byte that corresponds to an ASCII codepoint actually is an ASCII codepoint). This includes ASCII itself, latin1 and UTF-8.

- ripgrep works best with UTF-8. For example, ripgrep's regular expression

engine supports Unicode features. Namely, character classes like

\wwill match all word characters by Unicode's definition and.will match any Unicode codepoint instead of any byte. These constructions assume UTF-8, so they simply won't match when they come across bytes in a file that aren't UTF-8. - To handle the UTF-16 case, ripgrep will do something called "BOM sniffing" by default. That is, the first three bytes of a file will be read, and if they correspond to a UTF-16 BOM, then ripgrep will transcode the contents of the file from UTF-16 to UTF-8, and then execute the search on the transcoded version of the file. (This incurs a performance penalty since transcoding is slower than regex searching.)

- To handle other cases, ripgrep provides a

-E/--encodingflag, which permits you to specify an encoding from the Encoding Standard. ripgrep will assume all files searched are the encoding specified and will perform a transcoding step just like in the UTF-16 case described above.

By default, ripgrep will not require its input be valid UTF-8. That is, ripgrep can and will search arbitrary bytes. The key here is that if you're searching content that isn't UTF-8, then the usefulness of your pattern will degrade. If you're searching bytes that aren't ASCII compatible, then it's likely the pattern won't find anything. With all that said, this mode of operation is important, because it lets you find ASCII or UTF-8 within files that are otherwise arbitrary bytes.

Finally, it is possible to disable ripgrep's Unicode support from within the

pattern regular expression. For example, let's say you wanted . to match any

byte rather than any Unicode codepoint. (You might want this while searching a

binary file, since . by default will not match invalid UTF-8.) You could do

this by disabling Unicode via a regular expression flag:

$ rg '(?-u:.)'

This works for any part of the pattern. For example, the following will find any Unicode word character followed by any ASCII word character followed by another Unicode word character:

$ rg '\w(?-u:\w)\w'

ripgrep has a lot of flags. Too many to keep in your head at once. This section is intended to give you a sampling of some of the most important and frequently used options that will likely impact how you use ripgrep on a regular basis.

-h: Show ripgrep's condensed help output.--help: Show ripgrep's longer form help output. (Nearly what you'd find in ripgrep's man page, so pipe it into a pager!)-i/--ignore-case: When searching for a pattern, ignore case differences. That isrg -i fastmatchesfast,fASt,FAST, etc.-S/--smart-case: This is similar to--ignore-case, but disables itself if the pattern contains any uppercase letters. Usually this flag is put into alias or a config file.-w/--word-regexp: Require that all matches of the pattern be surrounded by word boundaries. That is, givenpattern, the--word-regexpflag will cause ripgrep to behave as ifpatternwere actually\b(?:pattern)\b.-c/--count: Report a count of total matched lines.--files: Print the files that ripgrep would search, but don't actually search them.-a/--text: Search binary files as if they were plain text.-z/--search-zip: Search compressed files (gzip, bzip2, lzma, xz). This is disabled by default.-C/--context: Show the lines surrounding a match.--sort-files: Force ripgrep to sort its output by file name. (This disables parallelism, so it might be slower.)-L/--follow: Follow symbolic links while recursively searching.-M/--max-columns: Limit the length of lines printed by ripgrep.--debug: Shows ripgrep's debug output. This is useful for understanding why a particular file might be ignored from search, or what kinds of configuration ripgrep is loading from the environment.